Post COVID-19 images of Pope Francis

The first global pandemic of the digital age arrived suddenly. The world was stopped in its tracks by an unnatural suspension of activity that interrupted business and pleasure.

Aug 01, 2020

––Continued from last week

The first global pandemic of the digital age arrived suddenly. The world was stopped in its tracks by an unnatural suspension of activity that interrupted business and pleasure.

“For weeks now it has been evening. Thick darkness has gathered over our squares, our streets and our cities; it has taken over our lives, filling everything with a deafening silence and a distressing void that stops everything as it passes by. We feel it in the air, we notice in people’s gestures, their glances give them away. We find ourselves afraid and lost.”

These are the words Pope Francis used to portray the unprecedented situation. He pronounced them on March 27 before a completely empty Saint Peter’s Square, during an evening of Eucharistic adoration and an Urbi et Orbi blessing that was accompanied only by the sound of church bells mixed with ambulance sirens: the sacred and the pain.

The Pope has also stated that the crisis period caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is “ a propitious time to find the courage for a new imagination of the possible, with the realism that only the Gospel can offer us.”

The thick darkness, then, allows us to find the courage to imagine. How was it possible to send out such a message in a moment of depression and fear? We are accustomed to the probable, to what our minds suppose should happen, statistically speaking. However, we often lack the vision of the possible, which is sometimes confined to the world of the imagination. We are not accustomed to dwelling in possibility, to use the words of Emily Dickinson. So we need a “realism” that breaks our “fixed or failing patterns, modes and structures” and inspires us to imagine a different world, “making all things new,” as the Book of Revelation says. “Are we willing to change our lifestyles?” the Pope asks.

There are seven images of Pope Francis’ post-COVID-19 imagination of the possible. In last’s week issue, we covered the first two. They were:

1. The boat in the storm

2. The new flame in the night

On this article, the remaining five images are explained.

3. The underground and the mountains

In the interview given to Austin Ivereigh, available through the Civiltà Cattolica website, Francis said: “I’m going to dare to offer some advice. This is the time to go to the underground. I’m thinking of Dostoyevsky’s short novel, Notes from the Underground. Go underground to see the earth and understand its dynamics: this is necessary. These are dynamics that the Pope reveals by referring to photographs: “A photo appeared the other day of a parking lot in Las Vegas where the homeless had been put in quarantine. And the hotels were empty. But the homeless cannot go to a hotel. That is the throwaway culture.” And another one: “In Rome recently, in the midst of the quarantine, a policeman said to a man: ‘You can’t be on the street, go home.’ The response was: ‘I have no home. I live on the street.’”

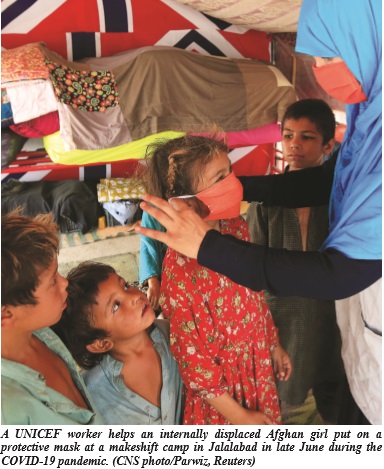

The call is to open our eyes, to see: “To ‘see’ the poor means to restore their humanity. They are not things, not garbage; they are people. We can’t settle for a welfare policy such as we have for rescued animals.” So “going underground” means passing “from the hyper-virtual, fleshless world to the suffering flesh of the poor.” Seeing the waste leads to touching the flesh.

Addressing the issue of young people in that interview, Francis proposed a reversal of the top/down perspective, and indicated the direction of the gaze from below. He asks the young people, in fact, to have “the courage to look ahead.” And he says this by quoting Virgil. When Aeneas has lost everything following defeat in Troy, two paths lie before him: remain there to weep and end his life, or “follow what was in his heart, to go up to the mountain and leave the war behind. It’s a beautiful verse: Cessi, et sublato montem genitore petivi ‘I gave way to fate and, bearing my father on my shoulders, made for the mountain.’”

4. The war of poets

In a context in which the “fight” against the virus has been treated in war-like terms, which describe it as an invasion by an enemy power, the citizen becomes a soldier and the helper becomes a hero. The logos gives way to polemos. In the semantic field generated by the word “war,” the one who “falls” and becomes ill is a loser. The sick person is a loser.

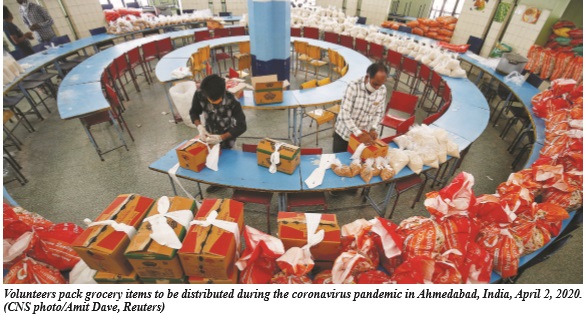

The Pope does not shirk the use of the war metaphor, but he makes it perform a pirouette that alters its usual meaning. “In these days, full of difficulties and deep anguish,” he wrote in a letter to the Popular Movements on Easter Sunday, “many have used war-like metaphors to refer to the pandemic we are experiencing. If the struggle against COVID-19 is a war, then you are truly an invisible army, fighting in the most dangerous trenches, an army whose only weapons are solidarity, hope, and community spirit, all revitalising at a time when no one can save themselves alone. As I told you in our meetings, to me you are ‘social poets’ because, from the forgotten peripheries where you live, you create admirable solutions for the most pressing problems afflicting the marginalised.”

It is very interesting how the metaphor is taken up and emptied from the inside, and resolved in its opposite. Who is the invisible army that fights in dangerous trenches? It is the poets, the “social poets.” The Pope’s expression is unusual and must be explored. Who is the poet? It is the person who makes creative use of language: he or she uses everyone’s words, but to express something in a divergent way, an alternative to ordinary speech, to common or dominant narratives.

It is necessary to create a narrative that knows how to take risks and that corresponds to the appeal: “Roll up your sleeves and keep working for your families, your communities and the common good.” Francis repeated this concept in other words during the Regina Coeli on May 24: “Encourage us to tell and share constructive stories that help us to understand that we are all part of a story that is larger than ourselves, and we can look to the future with hope if we truly care for one another as brothers and sisters.”

The Pope uses the poetic-social paradigm to oppose the technocratic ones that put the state or the market at the centre: “Now, more than ever, persons, communities and peoples must be put at the centre, united to heal, to care and to share,” writes Francis. The action of the army of poets aims at “healing,” that is, it has a therapeutic value. Healing consists in “taking back control of our lives,” in shaking “our sleepy consciences,” in producing “a human and ecological conversion that puts an end to the idolatry of money and places human life and dignity at the centre.”

5. The perfumed anointing of service

A fourth image used by Francis is the one that emerges from an article he wrote in the magazine Vida Nueva on April 17, 2020, entitled “A Plan to Resurrect.” In this very rich text, the Pope affirms that the pandemic situation that “overwhelmed” us evokes in the believer a listening to the “overflowing” proclamation of the resurrection.

What was the pontiff focusing on? “We have seen,” he writes, “the anointing poured by doctors, nurses, supermarket employees, cleaners, caregivers, providers of transport, law and order forces, volunteers, priests, religious men and women and so very many others who had the courage to offer everything they had to give a little care, calm and soul to the situation.” Here the list appears again. But those who were described on March 27 as “exemplary companions for the journey,” now, on April 17, are those who pour the oil of anointing, perfumed like chrism, that is, the oil of consolation and blessing. After all, companionship is a blessing. And “the poured perfume” has “more capacity for diffusion” than the despair that threatened the disciples at the death of the Master. Thus “it is enough to open a crack so that the anointing the Lord wants to give us can expand with unstoppable force and allow us to contemplate the painful reality with a renewing gaze.”

It is the perfumed anointing of service that accompanies sorrowful humanity and allows us to be “creators and protagonists of a common history.” This is once again the key point: the anointing leads to the construction of a common history that reveals human brotherhood. Francis’ message is strongly affirmative in this sense. The time of the virus becomes a kairos, a favourable moment of which to take advantage. From the analysis of the “nights” of the world, we pass to the vision of the future that awaits us, “if we act as one people.”

The anointing “opens horizons” and “awakens creativity,” which for its rhythm has the “beat of the Spirit.” The political discourse becomes spiritual and prophetic; the Lord “wants to generate in this concrete moment of history” the dynamics of “new life.” And so – as we already mentioned at the beginning of this reflection – “this is the propitious time to find the courage for a new imagination of the possible, with the realism that only the Gospel can offer. The Spirit, who does not allow himself to be locked up or used within fixed or transient schemes, modalities and structures, proposes to unite us to his movement capable of ‘making all things new’ (Rev 21:5).” Hence the appeal: “Let us take this trial as an opportunity to prepare for the tomorrow of all, without discarding anyone: of all. This is because without a vision for everyone, there will be no future for anyone.

Imagination of the possible

6. The window and the society of preventive medicine

A negative image that we highlight was used by Francis in his Letter to the priests of the diocese of Rome, sent on May 30 because it had not been possible to celebrate the Chrism Mass. In a dense text, he treasures the intense communication he had with the priests of his diocese by e-mail and telephone. From these “sincere dialogues” he was confirmed in the fact that the “necessary distance was not synonymous with withdrawal or closure into the self that anesthetizes, puts mission to sleep and turns it off.”

Indeed, “the notion of a ‘safe’ society, carefree and poised for infinite consumption” has been challenged by the virus, “revealing its lack of cultural and spiritual immunity to conflict.” One should not delude oneself that the questions that have emerged in this time will be answered with the reopening of activities. Rather, it will be indispensable to “prepare and open up the path that the Lord is now calling us to take.” It is not possible, therefore, to remain extraneous to these realities by simply “looking out at them from the window.” Here is the negative image, the window as synonymous with distance.

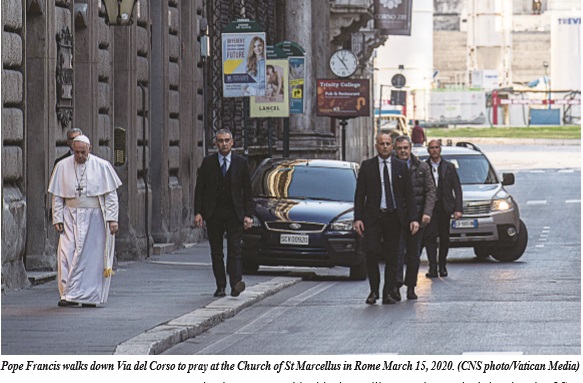

The Pope instead praises the priests “soaked by the raging storm.” “Soaked” is the key word. It is not the balconyar, as the Pope likes to say in his Argentine porteño dialect, but the Church being on the road, callejera. Francis actually gave this message by placing his body, even his limp, at the service of a message of closeness and hope. On the afternoon of Sunday, March 15, walking along a stretch of Via del Corso, as if on pilgrim age, he reached the church of San Marcello al Corso, where there is the miraculous Crucifix that in 1522 was carried in procession through the districts of the city to end the “Great Plague” in Rome. In his prayer Francis sought the end of the pandemic. His spiritual authority was concentrated in his perfect isolation at a time when bodies had disappeared from the streets. Those steps were necessary to offer up to Christ on the cross our lockdown and prophetically foreshadow the paved road after COVID.

“Looking out at them from the window” instead confirms the narrative of preventative medicine, being safe, which is brought about by distancing and anesthetizing. The logic of the window must be overcome by an immersive logic, which “soaks” and involves from below, inviting us to elaborate new ways and new lifestyles.

7. The pandemic as a metaphor for understanding the world

Finally, we note how the pontiff in his speeches used not only metaphors to talk about the pandemic and its effects, but the pandemic itself as a metaphor for diseases in general and for the evils of the world: “But there are so many other pandemics that make people die and we don’t notice – said Francis in Santa Marta on May 14, 2020 – we look the other way.” And, after recalling some data, he con tinued: “May God have mercy on us and stop the other awful pandemics: of hunger, of war, of children without education.” In the homily for the Second Sunday of Easter, the “pandemic” detected by the Pope was that of the virus called “indifferent selfishness.” There is a sort of pandemic of the spirit and of social relations, of which the coronavirus has become a symbol and image.

Conclusion

Here again, then, are the seven images: the boat, the flame, the underground, the war (of the poets), the perfumed anointing, the useless window, the pandemic itself as a metaphor. These are the tesserae that make up the mosaic of an imagined, possible world that calls our attention, on the one hand, and on the other, encourages us: “Faith grants us a realistic and creative imagination, one capable of abandoning the mentality of repetition, substitution and maintenance” and pushes us to “face reality without fear.”

Francis has indicated with his seven images – not in a Pelagian and voluntaristic way, but relying on the work of the Spirit – a firm trust in the human person, and in reason that can understand problems, and in the ability to act with competence and determination.

The Pope has enhanced the time of waiting, the “spinning wheel” of our operating system, to become a “mirror” for a world in crisis. And to do this he had to interpret chaos. In the end, how ever, the mirror is the Gospel itself. Whoever does not see it and relegates Francis’ discourse to “politics” without faith falls into a visual aberration, into that strabismus caused by the lack of fusion that allows the images of the two eyes to unite into one vi sion. Francis looks at the world as the vicar of Christ, that is, with the eyes of Christ; and he does so theologically, combining an apocalyptic interpretation, an invitation to conversion and an Easter perspective of death and resurrection.

The task for the Church is what the Pope had already indicated in the interview with La Civiltà Cattolica in 2013: to be a “field hospital” to heal and tend the wounds of humanity. Believers are not called to multiply pious words, but to give Gospel solutions, moved and inspired by Revelation. This is the social doctrine of the Church. This is the conversion of the gaze. And this is the time of a different world, which requires both the recognition of global vulnerability and the imagination proper to Gospel realism. — By Antonio Spadaro, SJ, La Civilta Cattolica

Total Comments:0